Federal Reserve data shows sharp rise in amount Americans 65 and older owe

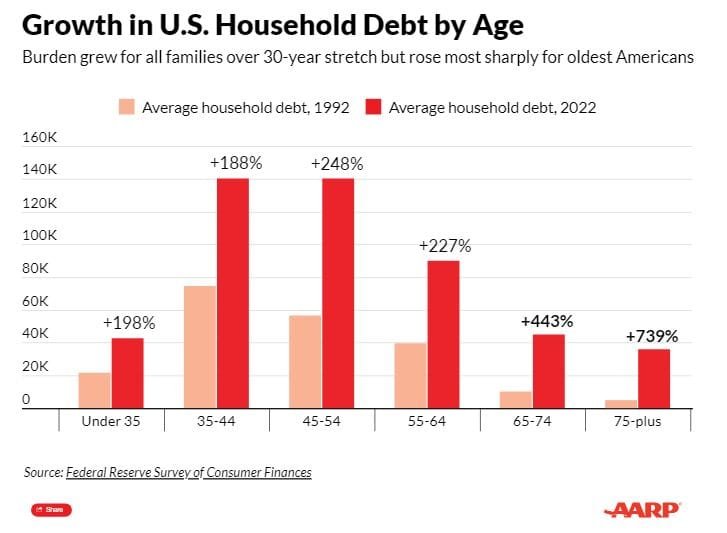

Americans across generations are carrying more debt than they did three decades ago, according to Federal Reserve data, but the rise has been especially steep among the oldest age groups.

The Fed’s most recent Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) found that among all groups younger than 65, debt roughly doubled from 1992 to 2022. That’s in line with inflation over that time.

But debt more than quadrupled in households headed by people aged 65 to 74 in that period (from $10,150 to $45,000 per household, on average), and for those 75 and up it has increased sevenfold (from just under $5,000 to $36,000).

Older adults are also considerably more likely to have debt now than they were a generation ago. Fifty-three percent of households headed by someone 75-plus had debt in 2022, compared to 32 percent in 1992. For the population at large, the increase was just a few percentage points.

“There are a lot of folks who just don’t have enough money put away,” says Jason Athas, manager of educational programs at Debt Management Credit Counseling Corp., a Florida-based nonprofit that provides debt relief and counseling services.

As a result, he says, he is seeing more older adults struggling to keep up with their costs. Research by AARP and others bears him out.

An October 2023 AARP study found that 65 percent of people 65 and older who have debt consider it a problem, including 29 percent who call it a major problem. According to a July 2024 report from the Nationwide Retirement Institute, a research and consulting arm of the insurance company, nearly a third of retirees expect to be less financially secure in retirement than their parents or grandparents.

“Credit card debt is one of the biggest problems seniors have today,” Athas says.

Inflation impact

Household debt among those 75 and older has declined since 2010, when it more than doubled to nearly $41,000 on average in the wake of the Great Recession, according to the SCF, which the Fed conducts every three years. Their debt had declined sharply by 2013 but has risen steadily since, subsequent surveys showed.

Runaway inflation in 2021 and 2022, and the Federal Reserve’s campaign to tamp it down by sharply raising interest rates, have played a part, financial professionals say.

“We’re all impacted by the accelerated cost of living,” says Hector Madueno, financial education manager at SAFE Credit Union in Northern California.

While painful for all consumers, higher prices are more easily absorbed by people in the workforce because wages typically rise in tandem with prices. “Retirees are less likely to have this buffer,” says Fred Perez, chief lending officer at Southern California’s First City Credit Union. The ultralow interest rates in place before the inflation spike also contributed to higher debt by prompting more older homeowners to tap into their accrued housing equity.

“Part of why we’re seeing more mortgage debt at older ages is [because] the nature of how people manage their debt across a lifespan has changed,” says Lori Trawinski, director of finance and employment at the AARP Public Policy Institute.

“There’ve been a lot more refinancing opportunities that didn’t exist in the ’60s and ’70s, so now it’s rare for someone not to refinance their mortgage if they’re in their home a long time,” she says. “People have become much more used to carrying a mortgage into their retirement years.”

Mortgages account for roughly three-quarters of the debt held by Americans 70 and older, according to a May 2024 report from the New York Fed.

Recession legacy

Economists and financial advisers tend to broadly segment debt into “good” and “bad” categories. Low-rate and fixed-rate debt such as mortgages are generally considered less worrisome than revolving, high-interest debt such as a credit card balance.

As a credit counselor in the aftermath of the Great Recession, Athas saw people rely on credit cards after job losses. Older workers in their peak earning years struggled to rejoin the labor force and attain their former income. For many, the result was a legacy of debt.

Today’s high interest rates are exacerbating that, he says: “If they’re carrying a balance and not paying it off, they’re getting hit with a good amount of interest on that debt.”

Nearly half of boomers have credit card debt, and nearly two-thirds have been carrying it for more than a year, according to a June 2024 Bankrate survey.

Even so-called good debt like home loans can pose a unique threat to the oldest borrowers because they have fewer options to increase their income if they find themselves struggling to make payments.

Nearly 40 percent of people 80 and up pay at least 30 percent of their income on housing, compared to 32 percent of the overall population, says Jennifer Molinsky, director of the Housing and Aging Society Program at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Borrowers who have already tapped their home equity or taken out loans to manage older debts without changing their spending habits risk digging themselves in deeper, Perez says. “They don’t curtail their spending. That’s a particularly troublesome concern.”

Steps to rein in debt

Advisers use a metric called debt-to-income ratio to evaluate a person’s financial health. As a rule of thumb, many lenders look for a ratio of no more than 36 percent, meaning the total amount you owe each month — including mortgages and home loans, student loans, credit cards and other debt — should not exceed 36 percent of your monthly income.

The recent rise in interest rates has scrambled this math for many older homeowners, a prospect that worries finance pros like Madueno. “As everything rises and people rely more frequently on their credit cards, people don’t take a look and see what their rates are,” he says.

Still, there are steps older adults can take, in the run-up to retirement or during it, to tackle debt before it becomes unsustainable.

Just the act of making a budget can be eye-opening, says Ryan Derousseau, a financial adviser at United Financial Planning Group in Hauppauge, New York. “If you haven’t learned how much you can spend on a month-to-month basis, no matter how much you earn, you’re going to run into this,” he says.

Ana Salazar, a goals coach at U.S. Bank, helps people identify additional money in their budgets by targeting items like unused subscriptions on automatic renewal. “Once we’re able to uncover those things and stop them, they have a little extra money they can use to pay down debt,” she says.

Nonprofit credit counseling organizations can negotiate with credit card companies to lower interest rates and waive penalty fees. “We can eliminate a lot of what they are spending on a high-interest credit card,” Athas says, which makes it easier for people to pay back the borrowed principal more easily.

Consolidating credit card debt into a lower-rate instrument like a personal loan also can reduce what you spend on interest. According to the Federal Reserve, the average interest assessed on credit cards in the second quarter of 2024 was 22.76 percent, a near record high. “If we can move that down to a 7 percent or 10 percent rate, that’s a heck of a lot better,” Derousseau says.

To make those solutions stick, however, it’s important to identify and address problematic spending behaviors so you don’t just run your credit card balances back up.

“People kind of get used to borrowing,” he says. “If you haven’t kicked that habit, you’re going to continue to be borrowing at 70 and 80.”

https://www.aarp.org/retirement/planning-for-retirement/info-2024/retirees-carrying-more-debt.html